I like board games mostly because they give me an excuse to hang out with my friends and have fun at the same time. Because of that, I highly value games with a simple rule set, something I can explain in 10 minutes or less and then get the game moving. Because of that, I really like games that are simple to play with relatively simple rules. Now you might think that means I don’t have many complex games, and that’s wrong. Really well designed games can have really simple moment to moment gameplay, but are complex enough that the optimal way to win is about as obvious as a solving world hunger (see the relatively new game “Azul” for a good example of this. In “Azul” every player only has 1 move they can make for the entire game, and yet it is very difficult to know how to win).

And it’s this combination of simplicity with complexity I value because, as the owner of ALL the board games, I’m often playing the same ones over and over again with different groups of friends. I need games to be simple because I need to be able to explain how to play them for the 50th time to new players without going insane. But the catch 22 here is I also need them to have complexity or else get bored of a game very quickly.

Fortunately, board games really are the kings of this marriage of simplicity and complexity, and that’s probably due to their limitations. They can’t be as complicated as a video game because boardgames can’t have any automated parts or calculations. If you want a board game simulation of ruling a kingdom in Europe, you’re not going to find something like “Crusader Kings” (which has so many numbers and values that I suspect some of them must secretly be meaningless), you’re going to find something like “Scythe.” Though, some video games do try out the “simple to play, complex to win” mentality of board games (see “Into the Breach,” this game could quite literally be pulled out of your computer and put onto your table without any of the core rules or mechanics needing to be changed). This is why limitations and restrictions are, in my mind, a bit underrated as a creative tool, but that’s another story for another day.

All of this leads me to the following website, which polled 90,000 board gamers and asked them why they played games. I wasn’t surprised by most of what this website said or found. What was surprising was when I accessed a relatively large data set from BoardGameGeek, I found that a surprising number of board games are single player. That fit with none of my expecations. I don’t play board games to be alone. I play to socialize, or beat other players, and quanticfoundry’s poll doesn’t contradict my intuition when generalizing my tastes to the general board game buying public I don’t think. But BoardGameGeek’s data did (at first glance). So I wanted to do some basic digging.

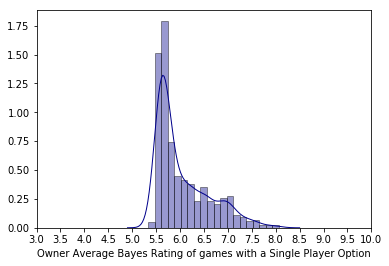

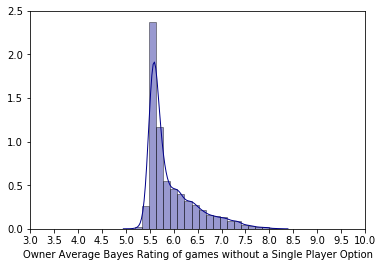

So first I wanted to find out if people liked games with that single player option more. So when I counted how people rated games with a single player option vs. non-single player counterparts we see this:

Which we can see pretty much with our eye alone that people rate games with a single-player option higher.

When we run a two sample t-test, just to be sure, we get a ridiculously low p-value of p = 5.98e-09. So the math agrees that the odds that games with a single-player variant do rate higher among consumers.

But, does that mean that those games sell better?

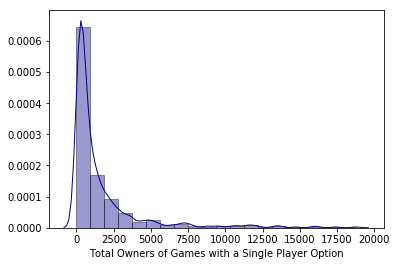

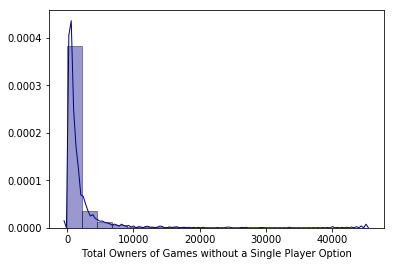

So gaming companies don’t really like giving out sales numbers, which I guess is understandable. But fortunately the dataset we were using also had a column numbering how many people OWNED a given game, so we can use that as a replacement for actual sale numbers.

I counted the number of owners of games with a single player option and plotted them as a histogram.

And you can still see that more people own copies of games with a single player option. If you test this with a two sample t-test, you get a statistically significant result of p = 0.00135. So, for now it seems to me that people like having a single player option.